Know that sinking feeling you get in the pit of your stomach when you realize that something really important is nowhere to be found? That’s what we get every time we ask a client for the password to his Macintosh, and the answer comes back, “I don’t remember.”

No one knows better than we do how many passwords a modern computer user has to juggle in the course of a day. Your email; your Facebook account; your banks; your photo collection; your credit cards; your pharmacy; hundreds of websites; and perhaps even your home thermostat.

The Mac OS does a reasonably good job of keeping track of (almost) every password associated with your life, by storing them automatically in a secure storage area called your keychain. That way, it can guard them against loss, present them automatically whenever needed, and keep your online life as manageable as possible.

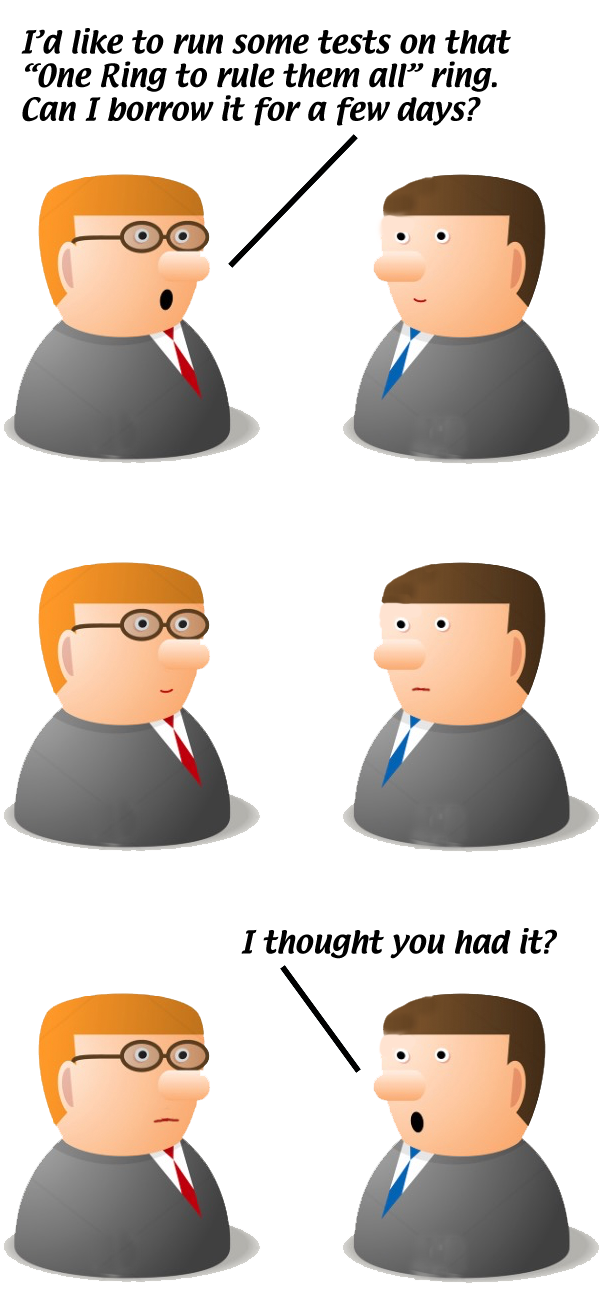

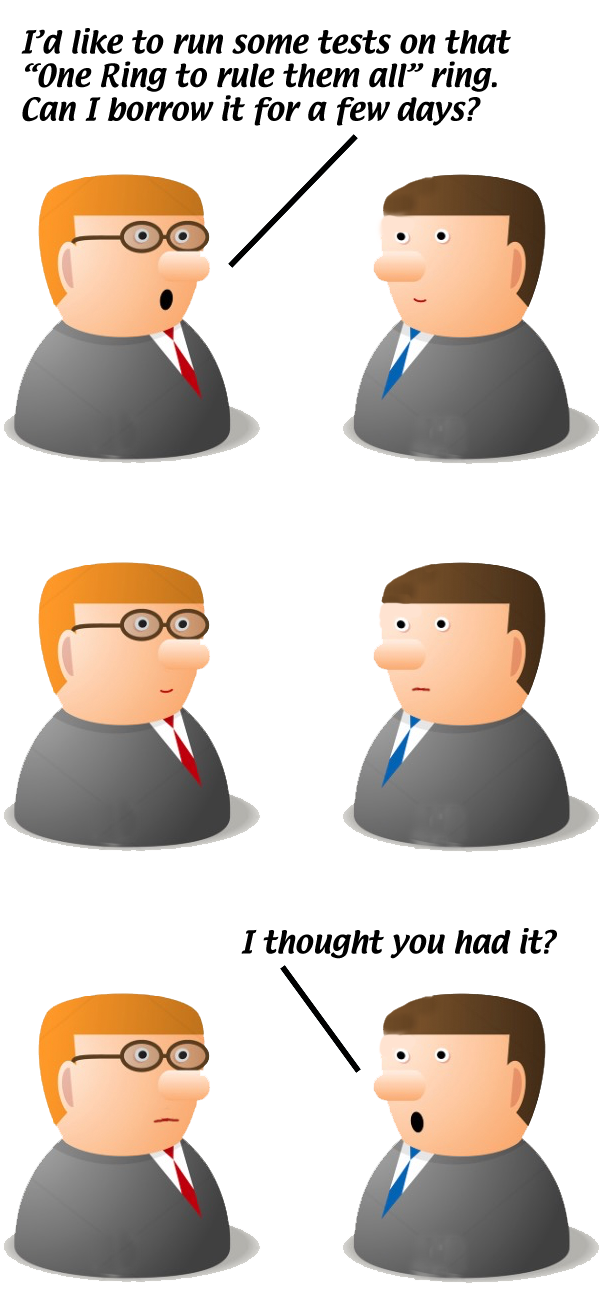

This keychain is secured by the one password that isn’t itself stored in the keychain: the password you use to login to your Macintosh. That makes your Mac password, in effect, the one password that rules them all. Given that password, you can automatically or manually look up any other password you own in that keychain. Without that password, your entire digital life is toast. Having this one password can mean the difference between having to pay for one or two hours of repair time, or many hours of repair time plus many hours of your own time.

“Can’t I just pick a new password?”

Sure you can. But if it were that straightforward, what would keep anyone who walked off with your computer from “picking a new password” for it, and thereby gaining access to every bank account and credit card you possess?

Yes, there’s a straightforward procedure to force a new password onto a Macintosh account. But when you next log into it, you’ll be notified that your keychain is inaccessible, because it’s still encrypted with your original password… which, of course, you still don’t know. With the old password, it would be a simple matter to unlock the keychain to encrypt it with the new password. Without it, every other password you need (and don’t remember on your own) is locked up forever.

Regular visits to the mental gymnasium

The one feature undoubtedly responsible for more cases of “I forgot my password” than any other is the automatic login. It’s seductive because it promises to make your daily online life easier, and does… until your disk drive fails, or you fall victim to a ransomware or tech support scam, and you need non-trivial reconstructive work done on your Mac. At that point, not knowing your password (because it’s been months or years since you actually had to type it anywhere) is an extra kick in the ribs that you really didn’t need while you were down. (We are seeing much the same syndrome now occurring among users of iPhones and iPads due to the availability of “Touch ID.” A password you never type is a password you soon forget.)

Our advice is never to enable automatic login. Computers get stolen; the kids and grandkids get into things they shouldn’t when nobody is around; and most importantly, typing in your password every time you log into your Mac is the best and most effective way to ensure you never forget it.

(If you’re currently running with automatic login enabled, and realize you have indeed forgotten your login password, contact us for help before doing anything else, including disabling automatic login. We can ensure that the contents of your keychain(s) are safe-stored for future accessibility before forcing your account to a new, known password.)

The Big Three passwords

Our advice to our clients is that they keep special track of three main passwords. With these passwords, you can recover most any other password you own. Just like you wouldn’t go for a drive without pocketing your license, you shouldn’t go online without having a record of these three passwords in a secure place.

- Your Mac login password, for all the reasons outlined above. This one will let you into your keychain, where most of the rest of your passwords are safe-stored.

- Your Apple ID (App Store / iTunes Store / iCloud) password. This password is a major special case, as it doesn’t exist in your keychain (unless you stored it there by hand as a note, which you may want to consider now that you know it’s possible). This is the password you need to reclaim all your purchased apps, tunes, and movies, and to reestablish connections with your iDevices.

- The password to your primary email address. If you forget or misplace either or both of the other two, this is the one you will need in order to receive responses to all the “reset my password” requests you will be making to all your secure websites (banks, etc.) as well as resetting your Apple ID password.

(If you’ve enabled iCloud Keychain, you also chose a six-digit iCloud Security Code which you may consider recording somewhere, as it won’t be in your Mac keychain—again, unless you put it there by hand. However, it’s not strictly necessary to have unless you’ve lost every other Apple device you own, as you can authorize any related activity from any of your Apple devices.)

Exercise records discipline

When we advise keeping copies of this information in a secure place, that also implies having a single place for the information, identifying which password is for what, and destroying obsolete versions of the passwords. As repair engineers, we are too often confronted with “records” consisting of multiple notebooks, index cards, and/or sticky notes containing several dozen total passwords, most of which have long since been superseded by others, with none of them identified as to account or function. To top it off, sometimes the working password is not even among them, having been recorded on an entirely separate piece of paper located elsewhere. A little organization and records discipline can mean the difference between a smooth service call and locking yourself out of your digital data indefinitely.

We hope you’ll consider the tips presented here and choose to adopt as many as possible in your own life, to keep your valuable data accessible to you while remaining secure from others.